In radical opposition to a non-fictional text in prose, whose object is usually rationality, lies poetry, whose purpose is often rewarded with incomprehension.

The poet never sits concerned with the logical exposition of an idea or feeling: what he seeks is the power of expression, the beauty. And it is better the poem whose meaning is suggested, – and not lucidly demonstrated, – making room for interpretation, in total opposition to the character of a scientific text.

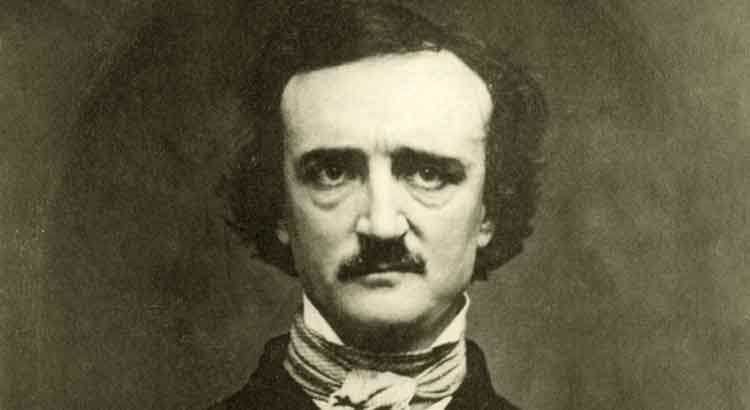

Well. Edgar Allan Poe, in this essay entitled The Poetic Principle, discusses his conception of poetry. Let us comment on some passages:

I hold that a long poem does not exist. I maintain that the phrase, “a long poem,” is simply a flat contradiction in terms.

Controversial. But if we understand a long poem as the concatenation of minor poetic units, Poe’s reasoning makes sense.

A poetic construction needs to be loaded with the same tone, with a well-defined goal, otherwise it will be less powerful. The poem, in this logic, boils down to a single movement of ascension.

Poe goes on to say where he thinks the value of a poem is:

The value of the poem is in the ratio of this elevating excitement. But all excitements are, through a psychal necessity, transient. That degree of excitement which would entitle a poem to be so called at all, cannot be sustained throughout a composition of any great length.

Just. Any rapture is, by definition, transitory. It is impossible to sustain excitement for long without losing its strength.

But what about the great epic poems?

Poe is categorical, referring to the Iliad:

In regard to the Iliad, we have, if not positive proof, at least very good reason, for believing it intended as a series of lyrics; but, granting the epic intention, I can say only that the work is based in an imperfect sense of Art.

Here, a note.

The apex of several of the great poems is subordinated to the construction of a preparatory atmosphere—at times, it can be said, unnecessary but often fundamental, and several of the best poetic constructions have their unity as a qualitative and fortifying character.

To waste verses to build as one does in prose will certainly damage the quality of a poem. But how can we deny, for example, that Paradiso, even composed in smaller chants, as suggested by Poe, does not have the effect amplified by being where it is in the Commedia?

Other interesting passage:

It by no means follows, however, that the incitements of Passion, or the precepts of Duty, or even the lessons of Truth, may not be introduced into a poem, and with advantage; for they may subserve incidentally, in various ways, the general purposes of the work: but the true artist will always contrive to tone them down in proper subjection to that Beauty which is the atmosphere and the real essence of the poem.

Morality, truth, and judgment are, for the poet, chains. What the poet feels or thinks must necessarily be in the background in the act of poetic construction.

That is to say: when composing a poem, the poet must turn his spirit to the construction of a supreme, harmonious, and full beauty, even if this requires a detachment of his own essence: a poem, if great, goes beyond the concepts of the artist who generated it.

____________

Read more: