Reading Heidegger, I felt like going out on the street and striking the first human being I met. Exasperating! And very funny the reaction, especially because of my enormous tolerance to what I dislike. Just before Heidegger, I had faced several of the most detestable pages I have ever read without a single violent impulse, without ever feeling the urge to tear up the book and physically assault a fellow man. What is the difference? The difference is that, in Rousseau’s pages, a man incapable of conceiving what would be honor or personal dignity, there was at least sincerity. And more than sincerity: there was style, conciseness, vigor in a prose that is undoubtedly one of the best in the French language. In it, reading the infamous is almost pleasurable. Rousseau knows how to build periods, to chain them, to make the logical progression of thought, and to expose it in a frank way. Heidegger did not. Heidegger hides behind a stupidly abstract language, whose most significant role is to make the banal look important. Heidegger affects methodical accuracy through ridiculous circumlocutions, typical of the one who does not have much to say, and an attentive reading captures the farce. Heidegger fools the reader. But why the comparison? I almost forgot. Rousseau, whose main work could be subtitled “The supreme foundation of demagogy,” whose lines are nothing more than dictating rules and saying how others should behave, still seems to me less vain than the one who, in ostensible linguistic imposture, builds an illegible work in order to impress.

Reflecting on Despair Vaccinates Against Despair

Reflecting on despair vaccinates against despair, reflecting on anguish slows down anguish, disillusionment only is harmful when untimely… and the mind seems to have the arsenal it needs to contain its own impulses. If moved by inertia, vulnerable; if put to work, prepared and resistant. The support it lacks is nothing but the fruit of its own creation. Thus, the idea of self-sufficiency really seems irresistible.

Prior and Regular Reflection Is Necessary

The collective shouting, deluding about the great questions of life, throws sand into the human spirit and diverts it from the essential. One who spends his days distracted and judging important second-rate problems, when violently struck by a great issue, loses control: he simply has not prepared himself. To know how to deal with the great events, not letting himself act stupidly and impulsively when surprised, prior and regular reflection is necessary. And reflection, in turn, demands detachment from collective shouting. Crossing the boundary of judgment, the individual analysis of the flock ends up inspiring gigantic compassion…

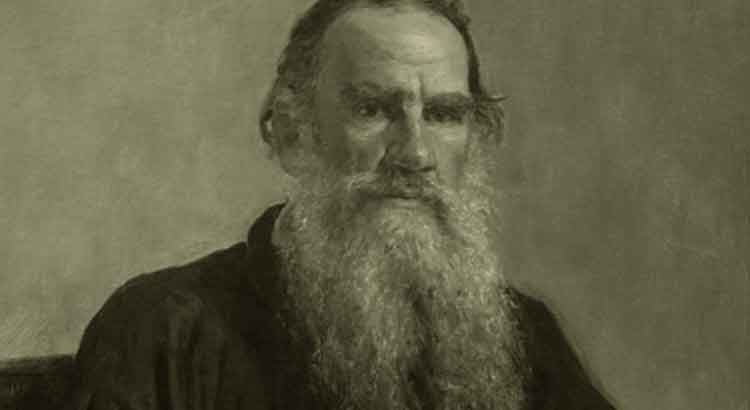

The Obsession With Artistic Technique

The obsession with artistic technique has taken me. What prevails in technique? to what extent does it matter? Suddenly, one of the most perfect scenes I have ever read comes to mind. I pull my version of Anna Karenina from the shelf, which has been lying there, motionless, since 2017. Certainly, I am no longer the same: in each of those years, what occurred to me was a drastic evolution in all matters. But I remember well the very strong impression I had of the scene. Let’s see. It takes me a few minutes to find it and, as I leaf through the work, I reflect again on the technique: there is a stylistic dimension impossible to translate; the pages I have in hand are an attempt to replicate the Russian original in Portuguese. Localizing the scene, my first impulse is to inspect its extension: exactly two chapters, which erupt after Vronsky says goodbye to Anna and, “restless,” to be “so full of feeling for Anna, that he didn’t even think what time it was”. He remembers that he would run a race, and realizes he is late. Then Tolstoy starts to narrate Vronsky, in this state of psychological tension, to be gradually taken from the competitive atmosphere. The crowded racecourse, the great expectation, everything contributes to exciting him. He dresses “without haste,” taking care not to lose his self-control. When he arrives at the racing scene, he encounters a “sea of carriages,” pedestrians, soldiers, and “the stands boiling of people”. He recognizes his opponents and, also, Anna: he does not come close to her, avoiding the loss of concentration. The atmosphere is impeccably painted, but what is most striking is that the great psychological tension that began the chapter only grows: each sentence shakes the nerves of Vronsky, who finds his mare also very agitated, “trembling as if she had a fever,” with eyes “full of fire”. All this in the chapter that precedes the race or, in other words, in the chapter that ingeniously describes the emotional and psychological aspect of the race. A voice resounds ordering the ride, and the seventeen competitors follow, nervously, to the race starting point, described in detail by Tolstoy: nine dangerous obstacles on an elliptical track of four versts. At the scream of the start, the animals start to run. Vronsky, who knows to be the target of all eyes, drops behind some horses and fights against the agitation of his mare. After the first obstacle, he “totally dominates the riding” and quickly overcomes his opponents, staying only behind his main competitor. All these movements are narrated magnificently: the acceleration, the stumbling of the horses, the jumps over the obstacles, and, especially, the psychological state of Vronsky, irritated by the second place. It does not take much for him to overtake his opponent and shoot ahead. He rises over the most dangerous obstacle keeping the tempo, rhythmic, under the cries of “Bravo!” Four hundred meters from the end of the race, knowing he has already won, Vronsky handles the reins to get well ahead of the others. He increases the speed of the mount so much that he flies under the last obstacle and, not being able to keep up with the speed of the mare, he breaks its spine letting himself fall on the saddle. He loses the race; doctors decide to shoot the animal down. The event, for Vronsky, remains “for a long time as the most painful and torturing memory of his life”. I finish the chapter with an impression as strong, as vivid as that of my first reading. The translation did not allow syntactic ornaments: and there is no need for them! The scene is masterfully chained: the arc of action, from the initial trigger to the outcome of the scene, encloses a particular tragedy, which can be read separately from the work without the slightest problem. The direct, objective narration stimulates the psychological at each paragraph, aided by adjectives and pictorial elements charged with emotional appeal. There is technique, this is evident: the construction was diligently planned, it stimulates with power and progressively the feeling in the reader. But I try to think that exactly this scene stands out from all the others. Where is the brilliance? why does it set the example of great art? how is it possible that, even in a translation, it has such a strong effect? And I incline to think that the great, in art, resides in what is written in universal language…