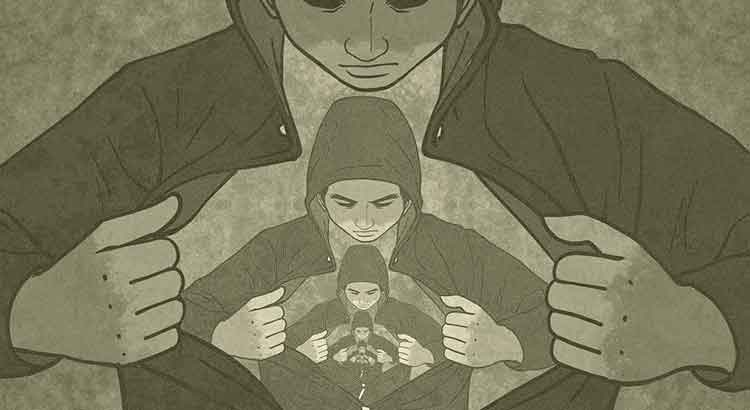

Some literary characters were fortunate to be classified by critics as the author’s alter ego. Others were born with the stamp from the master who gave birth to them. Alter ego… magical epithet capable of endowing any character with immediate depth, inciting his steps with the weight of real life. Funny! I cannot think of literature that does not contain, to a great extent, the weight of the author’s reality. It is simply impossible for me to imagine a writer writing by giving up his impressions of life, his experiences, his judgments about himself and others, the details of existence that only he notices, the observations he makes about the environment in which he lives. If he is painting an environment, for he will take as his basis an environment he has already witnessed or imagined; if he is describing a character, for he will use the examples that life has given him. Sensations: the simple fact of imagining them in depth is also to feel them, and it is not possible to judge that the author is immune to the feelings that he himself evokes. How would he know to describe them if he were unable to feel them? Thus, the alter ego, a term of multiple senses, can, in psychology, expose an interesting and complex deviation of personality, in literature usually exposes a personality obsessed with himself: the author.

____________

Read more: