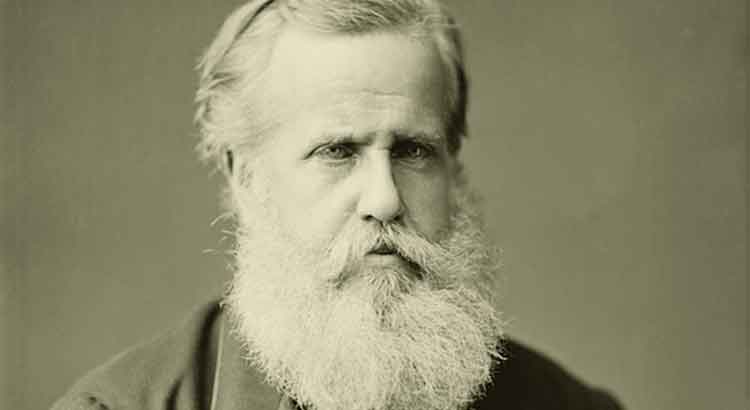

An inexplicable feeling of duty haunts me for a long time and demands me to portray the drama of Dom Pedro II. In my mind, I have already done it in verses, plays, movie scripts… But, in truth, I have done it because I cannot get rid of this obsession. Why? It is funny that, as usual, whenever I finally decide to execute the task, dozens of reasons make me abandon it. And the image of this man keeps coming to my mind while listening to Mozart’s Requiem. Seneca, Socrates and many others whose unjust end is obvious to my eyes do not inspire a similar feeling. It is Pedro II, and it has to be him for some reason. I do not know what to say…

Tag: literature

It Is Curious to Note That Many Great Artists…

It is curious to note that many great artists, especially in the 19th and 20th centuries, have had personal relationships with each other. Curious because, something that should configure normality, seems the exception. Previous centuries, in which distances seemed greater, saw themselves more or less dependent on a whim of fate to concentrate superior spirits in certain locations, as has marvelously occurred a few times in history. But still, something more is needed for a friendship to be established. And both whimsy and this something more seem to have abounded in the 19th and 20th centuries, when there were so many great names who knew each other, who were truly friends. I cannot notice it, without feeling sincere glee for all of them.

A Continuous Exercise of Patience

Poetry, this terribly difficult art, is a continuous exercise of patience. In poetry, haste is always the error. It is a real upheaval to know that, on the one hand, one must take advantage of spontaneous manifestations, which spring up in bursts and give great power to the verses; but, on the other hand, one must let the verses cool down, solidify, and then grind them calmly, adjusting the rhythm, changing words, refining expression. The stab wound of noticing a blemish caused by hastiness is extremely painful. A whole exhausting work, therefore, is spoiled when it is no longer possible to repair it. From it, to the artist, only failure, only frustration will remain. That is why poetic work is an exercise in self-control, in patience, where the poet must also act as a strategist, releasing and containing his impulses, suspecting himself even when he will conclude that he should not do it. And, still, it will not be enough…

Every Artist Has Inclinations and Deficiencies

Every artist has inclinations and deficiencies. There are themes that, by an innate disposition, come out naturally and brilliantly; others, however, present difficulties. Therefore, first of all, it is important that the artist is able to identify and classify them. Then, it is necessary to work to develop his weaknesses, and this is done by exercising the representation of what is opposite, exploring forms, taking risks. In art, of course, there are choices; but there are also weaknesses, and these, if not taken on board, in their own way, will always manage to become entrenched as obvious defects. Thus, will be complete the artist who, through effort, converts into strength that which is not natural to him.