The higher spirit, the more it develops, the more it increases the distance between itself and others, complicating relationships until they become impossible. Nietzsche confessed: “My humanity is a continuous victory over myself.” And the truth is that by developing, a spirit individualizes itself, and consequently distances itself from what is considered “common.” Ordinary men meet similar people with an ease that is almost a blessing, precisely because there is a psychological and behavioral similarity between them that allows immediate affinity. For those who deviate from the norm, everything is very different. Individualization, therefore, comes at the expense of bonds; it is therefore a drawback that must be considered. Whoever withdraws from men ends up becoming a stranger; reality is transfigured for him and if, on the one hand, he evolves spiritually, on the other he becomes incapable of sympathy for men, finally considering it a victory, as Nietzsche did with his usual sincerity, to simply tolerate their closeness.

Tag: philosophy

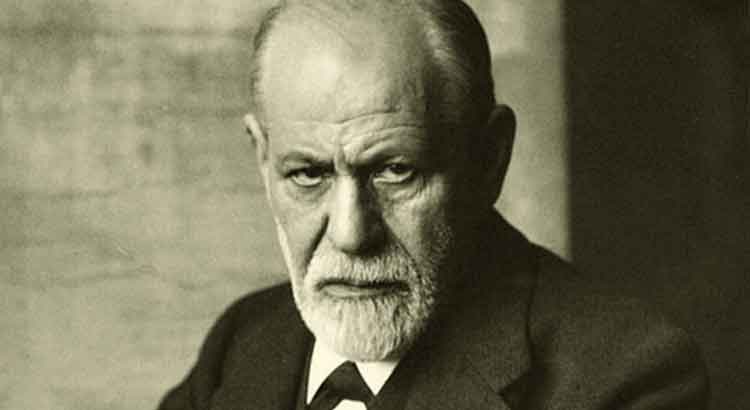

It Is Not Fair to Condemn Freud…

True, true: it is not fair to condemn Freud for exposing his patients’ weaknesses, for exploring them in search of justifications; after all, it would not be possible to outline solutions for them otherwise. Freud, thus, fulfilled an important task of a psychiatrist. The problem, however, and the reprehensible, is to analyze his work as a whole and find that there is no evidence of superior possibilities for the human being. Freud, not finding them in his patients, could have found them in himself, could have conceived them, even if in an ineffective will to overcome. But he did not; and, naturally, he validated in himself what he sketched as a human model. It is curious: Nietzsche is often called crazy, his “beyond-man” an absurd utopia, his will to power a delirium. And the same people who do not understand him approve Freud’s ideas. But there it is: both Freud and Nietzsche stripped themselves bare, and if in the latter we find a powerful impulse that propels us to truth, art, and above all to victory over ourselves, in the latter we are faced with a prostration before the weaknesses of flesh and mind, the fruit of lamentable spiritual misery. There is no escape: the work ends up fatally revealing the author’s inner self.

Various Doctrines Throughout History…

Various doctrines throughout history have understood and expounded that the central problem of human existence is to justify it, which is only done through life itself, through acts that serve as answers. The terminologies vary, as do the recommended paths; what does not vary is the notion of the need for this individual awareness and its implications, that is, the need to act in accordance with the aspirations of one’s intimate nature. Only in this way is possible an affirmation that is worth to the human being as a universal balm. Therefore, by the most diverse means, what the great doctrines teach is the orientation of life around a purpose—and man, defining it, has the mission to strive for its fulfillment.

It Is Really Admirable the Way Swami Vivekananda…

It is really admirable the way Swami Vivekananda interpreted and exposed Hinduism, integrating it, widening its arms and turning it into a legitimate catalyst of positive transformations for the human being. His Raja Yoga is the externalization of a noble, courageous, and stimulating philosophy. Very few authors are capable of deeply understanding the human condition and offering a solution that does not imply forced repression or the fading of the will. Swami Vivekananda, instead of leading to an aggravation of tensions or an eclipse of consciousness, proposes an active mental conduct directed to the elevation of one’s own nature. It builds, magnifies, encourages overcoming. What a great man!