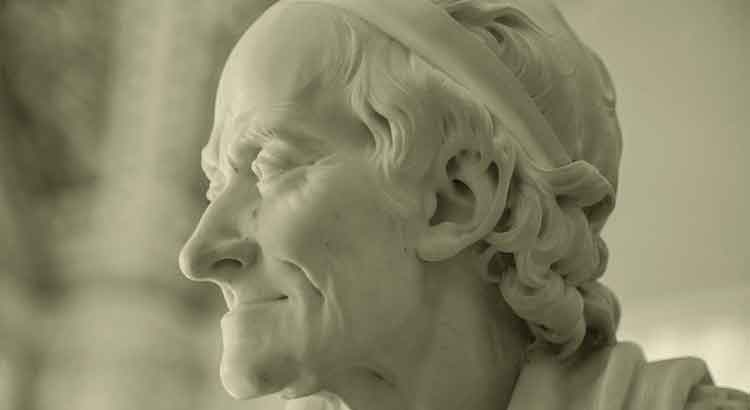

I jump from philosophy to astrology, from astrology to religion, and wherever I am there I find words of spite directed at Voltaire. Impressive! What the Ferney’s philosopher has achieved is an unmatched feat! I just read: “Voltaire, ce marveilleux ignorant, qui croyait savoir tant de choses, parce qu’il trouvait toujours le moyen de rire au lieu d’apprendre”. How not to sympathize or, rather, how not to fall into laughter? Time goes by, and my concept of this renowned philosopher who managed to irritate the world only grows. I believe it was Nietzsche who stressed the wisdom of Voltaire’s philosophical attitude, which always ended up stretching a smile on his face instead of frying his spirit by taking life and history so seriously. Smiling in the face of human stupidity: this is the very rare virtue that Voltaire, more than anyone else, knew how to practice.

Tag: philosophy

What Is Most Annoying About Agnosticism

What is most annoying about agnosticism, or rather agnostics, is the presumption of judging oneself to be a human model in the fullness of its potentialities. This, of course, is what points out the obvious. If the agnostic says that certain metaphysical or religious questions are unknowable to the human spirit, it implies that he knows it in its supreme degree of evolution. The possibility that there are human beings with faculties that he does not possess, or evolved to a higher degree than his own, never enters his mind. Instead of saying, “I am not able to understand metaphysics,” he says, “Man is not able to understand it.” It is the immodesty and narrowness of vision typical of inferior spirits…

Reticences…

No matter how great my respect for the author or how high the elevation of spirit that a dissertation produces in me, I never experience the feeling that I am facing the revelation of a truth. Is it a vice? An exaggerated and counterproductive skepticism? Or a perceptive limitation? It is true that the study of metaphysics takes the mind to a much more interesting plane than the plane of the so-called sensible reality; but what good is it, for a mind incapable of accepting formulas and opposed to affirmation? Reticences…

“I Will Not Die Today”…

Again, from Tsongkhapa:

Although we all have the thought that at the end of our life will come our death, each day we think, “I will not die today” and “Today too I will not die.” In this way, right up to when we are about to die, our mind holds on to the idea that we are not going to die.

If you do not take to heart an antidote to this, if your mind is obscured by such an idea and you think that you will remain in this life, then you will keep thinking about ways of achieving happiness and eliminating suffering in this life only, thinking, “I need such and such…”

Devoid of the perception of death, addicted to thinking that he will never die, the human being deprives himself of his essence, prevents the notion of the most important from blossoming within him. He is distracted by perishable futilities, wasting his time deluding his spirit. If for a moment he understands the true nature of death, he will no longer be able to live as before, no longer accept to get lost in worldly banalities, and will demand, even at the cost of his life, a reason that justifies his reality. Since there is death, since death annihilates the body, forces a final separation of possessions and relations, what is left? Is there anything left? Searching for answers, the being transforms his behavior and cancels the dangerous notion of “I will not die today”, moving on to the obsession: “If I die today… what then?”.