An honorable man, aware of his own dignity, if convinced politely and respectfully that a certain action is good and just, will willingly perform it, and be grateful for the advice. If, on the other hand, this same honorable man is ordered to perform a certain action under threat of punishment, he will react by instinct, driven by his own honor, in a manner contrary to the disrespectful one who threatened him. From this the natural conclusion: orders and threats are offenses to anyone who has a sense of dignity.

Tag: philosophy

Old Age, Disease and Death…

Old age, disease, and death; old age, disease, and death: the obsessions that paved the Buddha’s path to “enlightenment.” More than open eyes, it takes courage to confront them. Buddha understood that thought is worth nothing if it does not incur in action: from reasoning, he drew philosophy, and philosophy guided his conduct. Old age, disease, and death: everything that lives is condemned to torment, exhaustion, and suppression. The mind always wants to deceive itself; so let it suffer, let it daily embitter the conclusions of its judgment, until it has all to the last illusion torn from it! And thus, teaches the shrewd and enlightened psychologist, one escapes from the evil cycle that always results in suffering and destruction.

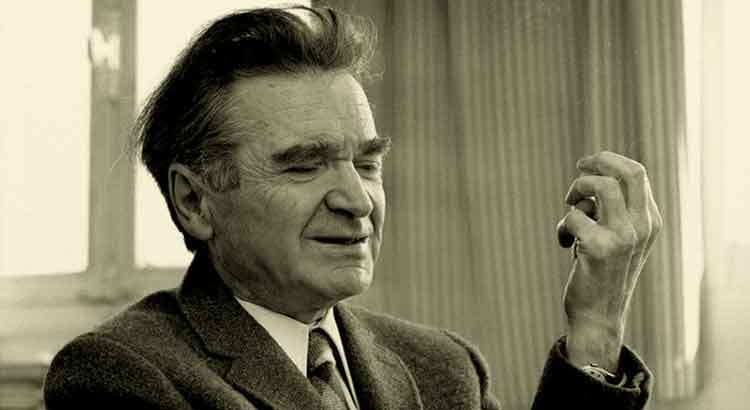

Notebooks, by Emil Cioran

My dear Emil Cioran said, in these Notebooks,—published posthumously,—that what left of a thinker is his temperament. What a beautiful observation! And I notice that, when I think of Cioran, what I remember is exactly his temperament. Impossible not to smile. In these Notebooks, where the human dimension of a philosopher who conceded several of his best pages to pessimism—or who, as Fernando Savater said, had the vocation of a heretic—are exposed practically all the scenes that come to my mind when I think of Cioran. There are almost a thousand pages that endow his work with a very rare coloring: it is the philosopher writing to himself, on one page, commenting on Buddha and Jesus Christ, on another, accesses of rage he has experienced in grocery stores, or unusual situations he has lived through. How can one not smile when seeing a wise man, after some editor rejects a preface on Valéry that cost him long hours of work, exclaiming to himself “I will have my revenge!”; or when seeing an athlete say that, returning from a twenty-kilometer walk, a girl offered him a seat on the train; or even, when seeing a master of sarcasm relate that, while talking to Jean-Paul Sartre, he heard from the Frenchman that his “Romanian grammar” was very good… I think of Cioran and what I remember from him is the supreme humor, which stands out above all his other intellectual qualities. Cioran, perhaps my favorite friend to accompany me through the darkness of thought, is also one of those who can most easily bring a smile to my face.

The Contrast Between Ancient and Modern Texts

It is amazing to note the contrast between ancient and modern texts. There is in the ancients an innocence—at least, this seems to us to be the right word—that causes us strangeness. We cannot understand them: there are texts that sound to us like they were written by children, or by beings from another race, inhabitants of another world. More: the ancients, for the most part, almost always sought to deal with the essential—something very rare in modern times, where literature is devoted to the trivial. The ancient texts are distinguished by the expression of an admiration, a reverence toward the reality that seems unimaginable to us. Modern man is devoid of the faculty of wonder: for him, existence is tedious and the world boring, old and banal.