Although much is to be gained and something can be learned about the mind through dream interpretation, one must be very careful not to fall into the tempting stupidity of rationalizing the non-rationalizable. It is certainly very useful to be aware of what goes on in states where consciousness volatilizes; there is much to be learned and the exercise is quite stimulating. What one must not do is succumb to the logical need to attribute meaning to spontaneous, unpredictable, irrational manifestations. A careful study, with time, points out connections, coincidences, and perhaps one or another circumstantial or emotional archetype particular to the analyzed mind. The rest varies as experience, temperament, real-life circumstances, recent events, and also the unlimited imagination vary. Considering all this, it must be admitted that, although often misused, this is an intriguing study, to say the least.

Tag: psychology

Gradations of Mental Manifestations

There are times when the idea is of little worth—but should be noted;—on further reflection, however, it is fair to discard it. At other times the idea seems weak, but later, re-examined with renewed breath, something valuable is drawn from it, and the weak is shown to be an important spark. Other times the mind manifests itself clearly, and the idea seems fair—from these the bulk of a work is extracted. And still other times, the mind manifests itself with such impetus that the artist, by restraining it, and not immediately focusing on what it tries to say, commits a crime against himself, and wastes what he can best extract from his mental manifestations. Attention and method are not enough; for the best use of the mind, is needed a disposition that goes against what is convenient.

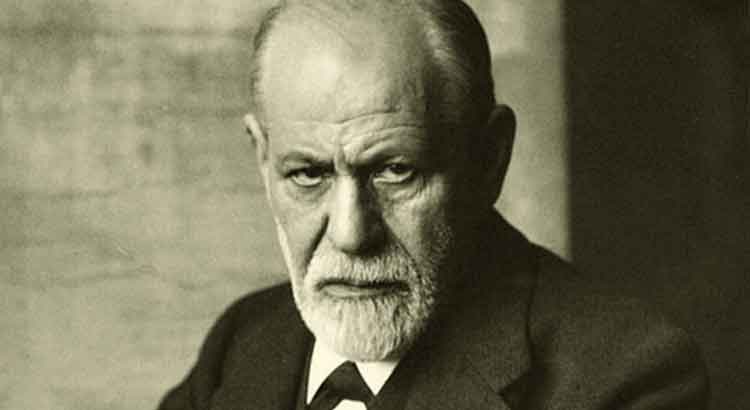

It Is Not Fair to Condemn Freud…

True, true: it is not fair to condemn Freud for exposing his patients’ weaknesses, for exploring them in search of justifications; after all, it would not be possible to outline solutions for them otherwise. Freud, thus, fulfilled an important task of a psychiatrist. The problem, however, and the reprehensible, is to analyze his work as a whole and find that there is no evidence of superior possibilities for the human being. Freud, not finding them in his patients, could have found them in himself, could have conceived them, even if in an ineffective will to overcome. But he did not; and, naturally, he validated in himself what he sketched as a human model. It is curious: Nietzsche is often called crazy, his “beyond-man” an absurd utopia, his will to power a delirium. And the same people who do not understand him approve Freud’s ideas. But there it is: both Freud and Nietzsche stripped themselves bare, and if in the latter we find a powerful impulse that propels us to truth, art, and above all to victory over ourselves, in the latter we are faced with a prostration before the weaknesses of flesh and mind, the fruit of lamentable spiritual misery. There is no escape: the work ends up fatally revealing the author’s inner self.

Enough With the Psychoanalysis!

I am browsing through an interesting work on psychology, when the references to psychoanalysis begin. God! I think I have reached the point where I can no longer stand it; the respect, the appeasing condescension is gone. I no longer find it tiresome, but depressing to keep looking at this mediocre human model proposed by Freud. A model stuck to the past, castrated of potentialities, for whom the future is nothing but the continuity of the lamentable present, the dragging of a mental slavery. I think of Buddha, or rather the young Siddhartha, whose relevance begins exactly after he became aware of life and his first manifestation of personality, who deliberated an abrupt and final break with the past—something impossible according to Freud. The ex-prince followed and trod his famous path, which bore absolutely no resemblance to and suffered absolutely no decisive influence from Siddhartha’s previous experiences. He became Buddha, and before Buddha someone different, someone whose steps manifested a free and resolute will, whose actions affirmed an ultimate detachment not only from the past, but from all the chains that Freud asserted as necessary components of his human model. He purified himself by climbing levels, adding to his experience the trials that made him more and more authentic, and less and less what he had been. Enough with the psychoanalysis!