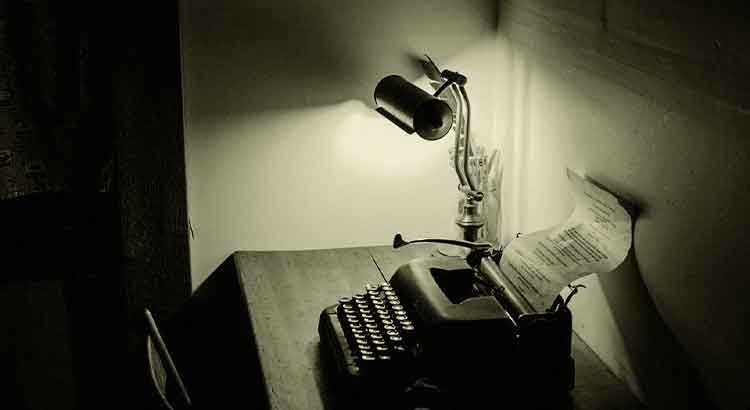

I beat these notes, always, in a static environment, in complete solitude. Everything rigorously immobile, except my naughty fingers. Just now, I thought of Fernando Pessoa. To my amazement, he appeared alive at my side. How? That is what I would like to know. I had thought, just before, of writing the following: “Existence is only justifiable to me as an answer to the authors I read, as the continuity of what they began.” And I would conclude that, despite being dead, they did not die. Then Pessoa bursts into my room. It is curious: a century ago, he was, like me, locked in a room in any corner of Lisbon, reflecting in solitude. Did he know the power of his verses? that they would resist, vigorously, the tyranny of time? He knew… Pessoa knew… And, naturally, in the eyes of the world, locked in a room, the poet “was not living”. I ask: and now, and for the rest of eternity, who lives and will live more: the guy who “lived,” or the poet who “was not living”? A century later, Pessoa, breaking the barrier of time and space, finds himself in my room. And if I open his Ode Marítima, I will be taken by a real and strong euphoria, more alive than any other sensation that a contemporary person could give me. And that is obvious: live little—very, very little—precisely those who seem to live a lot, in the eyes of conventional myopia…

____________

Read more: