If a shoemaker gave birth to hundreds of pages of metaphysical interpretations… I keep thinking: the writer who would dare to create a character like Jakob Boehme would fall into ridicule. It is inevitable. The reasoning does not admit of such a contrast; one would inevitably refuse to credit the narrative. Nevertheless, there it is… The mind’s first objection would be: “Such a thinker would never lower himself to manual labor.” Then it would go on, unbearable as usual: “Such reflections only spring from a nature one hundred percent devoted to the spiritual.” The conclusion: “Stupid and false history.” In the same way, it would judge if faced a living and talking Boehme. From this one can measure the vastness of the misery of objective thinking.

Tag: literature

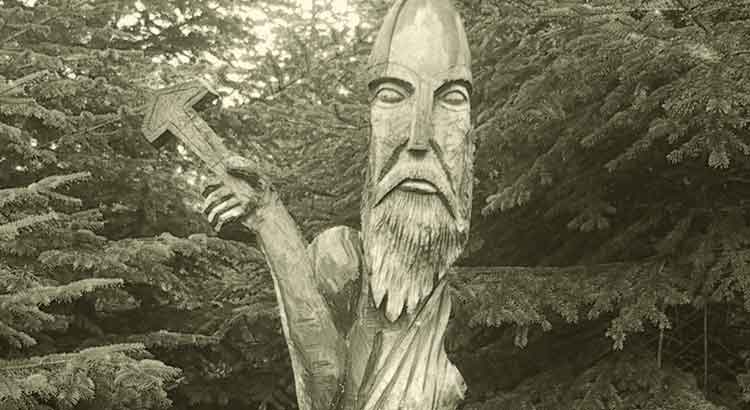

Thomas Carlyle’s Lectures

My rebellious fingers are itching after contact with Thomas Carlyle’s lectures. They want to answer him, they want to because they want to—but they will not. I regret to tell the slaves to control and content themselves with the brief irony they have already been allowed. Thomas Carlyle, indeed, is a remarkable and instructive intelligence; the interpretation of his “heroes” has much to add. I do not know why, analyzing him brings me Chesterton to mind: perhaps because both deserve, despite their patent incompatibility with me, my sincere handshake.

Nelson Rodrigues’ Way of Constructing Prose

Nelson Rodrigues’ way of constructing prose is curious. Whether in novels, short stories or even chronicles, it is clear his obsession with framing the text within a predefined aesthetic—he acts in prose as poets do in verse. The flow of his narratives almost always follows a protocol, and the result is a pronounced and unmistakable style. There was a time when I thought standardization was essential to great style. Today I see it a little differently. I admire regular constructions, but I believe I prefer variety: speed one day; the next slowness, a lingering cadence, commas instead of periods. Styles, formats, measures, not static dynamism or terminating sluggishness. What is difficult, however, is to identify masters in multiple styles, capable of satisfying, in a single work, the cravings of who is accustomed to finding comfort by shifting of shelves.

A Play and Sixty Short Stories by Force

A play and sixty short stories came out of me by force. As for the play, I hope to be the only one, and I have no intention of returning to that format. As for the short stories… it is impressive: it is very clear that the format bores me, yet I am aware that the work is not finished; I feel indebted, psychologically obliged to finish what I started, and it is certain that the time has not come to give me the final word. One play and sixty short stories by force: driven by the awareness that there are themes I cannot stop writing about.